- Length: the first thing to document while grossing the placenta is the length of the umbilical cord. About 1-2% of all umbilical cords will be less than 35 cm and those should be considered as a short cord (is the entire length of the cord was submitted). The short cord can be correlated with neonatal problems that may include placental abruption, cord hematoma, and, cord rupture. The long cord is longer than 70 to 80 cm. The long umbilical cord or excessively long umbilical cords can be associated with cord prolapse, cord entanglements, true knots, excessive coiling, or thrombosis due to entanglements many times. Clinical associations of the long cords include neurologic impairment, intrauterine fetal demise or growth restrictions; therefore, it is important to document it and correlate with clinical history.

- Cord diameter: The average cord diameter is about 1.5 cm. In excessively thin umbilical cords, usually, there is a decreased amount of Wharton’s jelly, and there is a possibility that the vessels will not be well protracted. Thick umbilical cords are many times only focally thickened and can be associated with cyst or hemorrhage.

- Twisting/coiling: The next important feature is coiling of the umbilical cord. The coiling can be left-sided or right-sided with an average coiling index is 0.2 per cm or one complete spiral in approximately 5 cm cord. Hypercoiled cords are seen in about 7.5% of the cases, hypocoiled cords and non-coiled cords are present in up to 5% of the cases. Any abnormal cord coiling may lead to restrictions of fetal movements, thrombosis, which further triggers neurological problems. Hypercoiling may lead to fetal demise or intrauterine fetal growth restrictions.

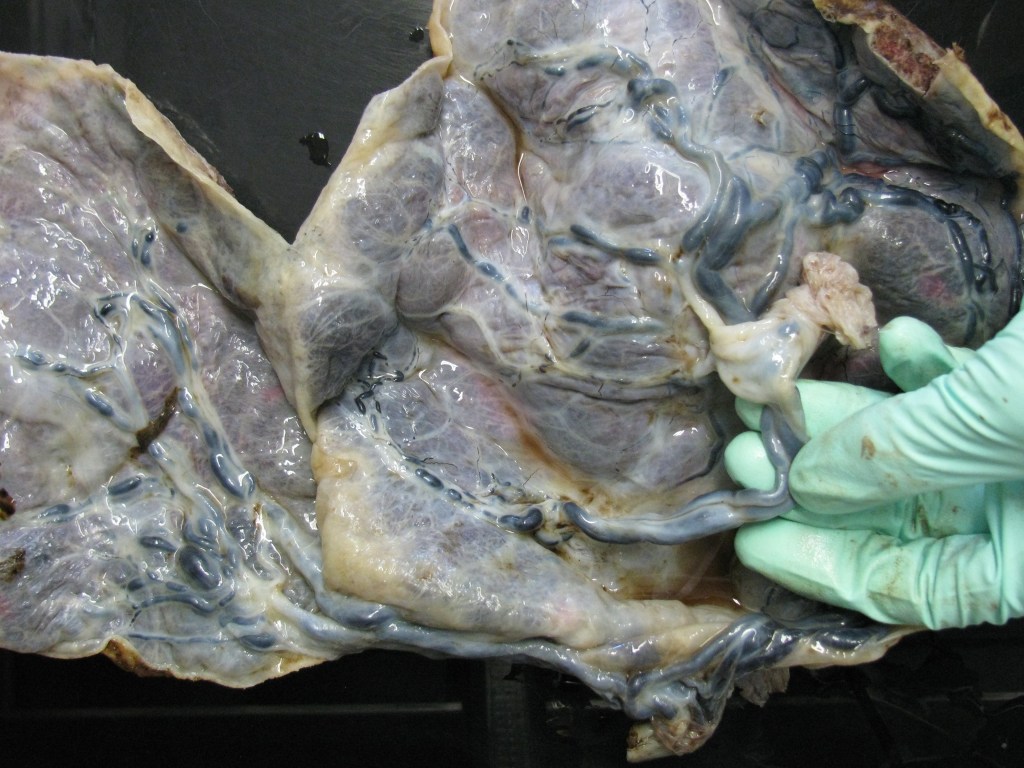

- Insertion of the umbilical cord: the umbilical cord is usually inserted centrally or eccentrically. Other sites of umbilical cord insertion include marginal insertion, marginal insertion with velamentous vessels, furcate insertion, interpositional insertion(cord inserts into membranes but does not lose Wharton’s jelly), and velamentous insertions. Insertions should be clearly noted on gross description. Eccentric and marginal insertions will not likely have a huge impact on a baby; however velamentous and furcate insertions may have consequences. About 1% of the cord’s insertion will be a velamentous or membranous insertion, which means that umbilical cord vessels will run freely in the membranes, and they lack Wharton’s jelly. This can lead to trauma at the time of delivery, nicking, and subsequently, thrombotic lesions.

Other findings: True and false knots, cysts, hemorrhage, or ruptures. If true umbilical knots are noted, one should describe if the knots are loose or tight. The tight knots are more serious and may have a more significant clinical impact by stopping the blood flow from the placenta to the baby.

- Cross-section of the umbilical cord usually reveals three (3) blood vessels (two umbilical arteries and one umbilical vein). If only two vessels are noted then the finding of the single umbilical artery should always be documented closer to the fetal end of the cord. Umbilical arteries tend to have anastomoses (Hyrtl’s anastomoses) and they tend to fuse little bit closer to the fetal end. The other finding that can be grossly examined is the presence or absence of thrombotic lesions in the umbilical vessels. The thrombotic lesions present as little white-tan plugs in the umbilical vessels. It is very important to document these. Presence of thrombosis in the umbilical cord is associated with fetal thrombotic lesions and with intrauterine fetal demise and intrauterine fetal growth restriction.

- Color: Surface green discoloration may suggest the presence of meconium in the umbilical cord. The white-yellow discolored umbilical cord should be sampled to rule out candida.

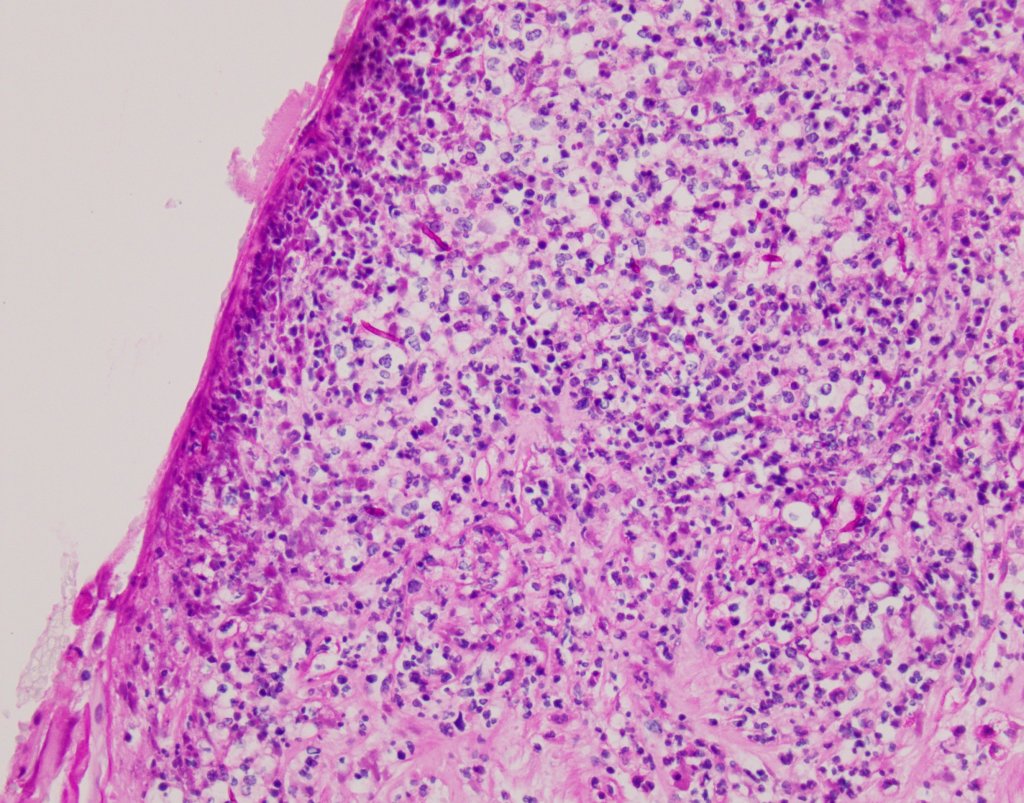

- Microscopically: the most common finding is inflammation of the umbilical cord (funisitis). Funisitis represents fetal response and may involve only umbilical vein or all three blood vessels with the spillage into Wharton’s jelly. If the acute information is reaching the surface of the umbilical cord, one should think about candida infection and perform special stains to highlight potential fungal microorganisms. Many times grossly described white lesions may correspond with squamous metaplasia of the amniotic epithelium.

Lastly, commonly seen umbilical cord remnants are allantoic duct (usually present centrally between umbilical arteries) and omphaloenteric duct (present at the periphery). They do not have substantial clinical significance.